Native Controls

Background

Despite the fact that views provides facilities for custom layout, rendering and event processing, in many situations we have found it desirable to use the controls provided by the host operating system (Windows to begin with). This is because these widgets already have many desirable properties: a system-native appearance that reflects the latest and greatest of the host operating system (e.g. using the same Win32 API as Windows XP on Windows Vista, native buttons receive glow animations when highlighted), handling for accessibility, focus, etc. Implementing new controls using views and Skia would be possible but it would take a long time to replicate all of this functionality, and we would have to update it for each new operating system release as well. So for areas of our UI where it wasn't important to have a distinctive, custom look, we have fallen back to native controls.

Historic Abstraction

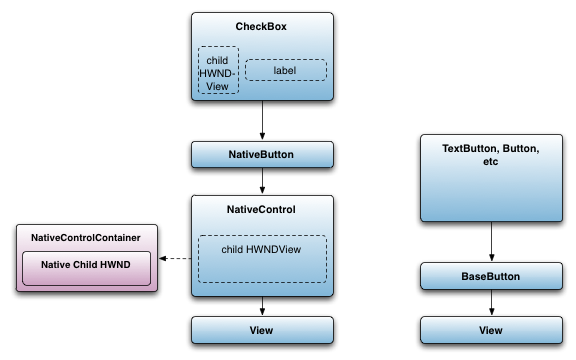

Historically, NativeControls have been used like so:

A base class, NativeControl, is the root of all NativeControls, like buttons, checkboxes, tree views, etc. This View subclass is Windows-specific and has a child View that is a HWNDView. This HWNDView hosts a HWND (NativeControlContainer) that is the parent of the actual native control HWND. The parent is responsible for receiving messages sent from the child HWND (e.g. WM_COMMAND, WM_NOTIFY etc) and forwarding these back to the NativeControl. This structure with the additional HWND was thought necessary because the assorted Windows common controls communicate message notifications to the client app by sending messages to the parent window. Back when Chrome had several different ViewContainer/root widget types, it made sense to encapsulate this handling at the NativeControl level. These days, there is only one root HWND type to be concerned with - WidgetWin, so it actually makes more sense to have it receive control notifications and forward them back to the NativeControl, rather than having to carry around all these extra HWNDs.

Another problem with this abstraction is related to the fact that Chrome has many different kinds of Buttons. Because NativeButton has no shared base class with the other Button base (BaseButton), much of the API ends up being slightly different. It'd be desirable to share a base class and then implement any of the NativeButton-specific methods in the derived class. However this is not possible due to this structure.

A final point of note: some NativeControl subclasses like CheckBox are a combination of system native controls and views components. To get proper transparent rendering behind the text label of a checkbox, the CheckBox has two child views - one which is the native windows control rendering only the checkmark section, and a views::Label child which renders the text. This structure has to be accommodated in any proposed modifications to this design.

Proposed Design

First of all, for any proposed design it's desirable to keep the API simple for users since native controls are used in very many places throughout Chrome. Ideally, using a native control is as simple as constructing one and adding it to your view hierarchy, which is the usage model that exists today for the windows-specific native controls and the views controls.

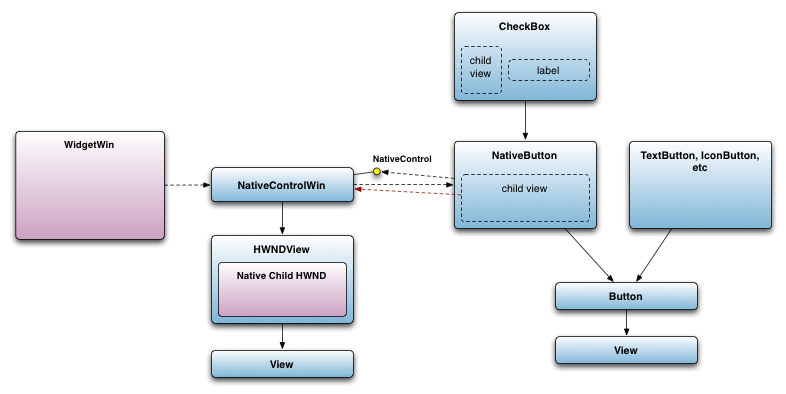

To achieve this, we use the PIMPL idiom to hide the native control implementation from the client in a setup like this:

In this world, NativeButton is a class derived from a base Button class just as the other Button classes are (e.g. TextButton, etc). It overrides various methods that require interaction with the native control, such as making the button appear as the default button in a dialog box etc. The interesting thing here is that the NativeButton itself is cross-platform code. The platform-specific details of implementing a native control are encapsulated behind a platform-neutral NativeControl interface implemented, in this example, by a new class NativeControlWin, a subclass of HWNDView that hosts the actual Windows native control. We avoid having an extra HWND here by stashing a pointer to the NativeControlWin on the attached HWND, and have the message handler in WidgetWin attempt to forward the message to the NativeControlWin directly if it finds such an association. The NativeButton implements a listener interface that receives higher level notifications from the NativeControl implementation about messages received from the operating system.

Since NativeControl is an interface not a class, it must provide a GetView accessor for the View that is to be parented as a child of the NativeButton, CheckBox or other view.

In this way, NativeButton can share a base class with other button types. A similar relationship can exist for other native controls where this is applicable, e.g. scroll bars, tree views, etc.

More Complex Controls

For controls more complex than buttons like, for example, TreeViews, there can be more elaborate code in NativeControlWin subclasses that handle messages from the native UI control and notify the view on the right half of the diagram as needed. Keeping the views on the right half of diagram platform neutral hides the complexity of maintaining platform-specific controls from consumers in the application - e.g. there is no need for ifdefs or factory methods at the call sites - the views can just be constructed directly and added to the view hierarchy:

void FooView::Init() {

button_ = new views::NativeButton;

button_->SetListener(this);

AddChildView(button_);

}

...

void FooView::Layout() {

button_->SetBounds(0, 0, width(), height());

}

vs the more baroque:

void FooView::Init() {

button_ = views::NativeButton::CreateNativeButton();

button_->SetListener(this);

AddChildView(button_->GetView());

}

...

void FooView::Layout() {

button_->GetView()->Layout(0, 0, width(), height());

}